This is a paper I presented on the 28th of April, at the Fantastic Narratives conference, Dalhousie University. Much thanks to Dr. Vittorio Frigerio and Dr. Elisa Segnini for accepting my paper and letting me present. And then there're a whole bunch of people who want to read it after I'm done presenting it. And I'm supposed to send it along for peer review. So I might as well have random people on the Internet also peer-review it.

In season 2 of Avatar: The Last Airbender, the protagonists, Aang, Katara, Sokka and Toph, are in the Earth Kingdom capital Ba Sing Se trying to seek an audience with the Earth King, and finding the bureaucracy blocking them. Then this conversation happens:

GIF set above reads:

Katara: The king is having a party at his palace tonight for his pet bear.

Aang: You mean, platypus bear?

Katara: No, it just says bear.

Sokka: Certainly you mean his skunk bear.

Toph: Or his armadillo bear?

Aang: Gopher bear?

Katara: Just... bear.

Toph: This place is weird.

The puzzlement towards The Bear that has only one aspect is a source of humour to audiences who are familiar with systems in which we can definitively declare something with a single aspect. In world-building exercises, writers are encouraged to draw directly from their knowledge and experiences, to reconstitute it into something different. This moment in the series was my starting point in considering how we often unthinkingly extend this understanding to something as fluid as concepts of culture and ethnicity.

Mass migration is not new, nor is cultural exchange. Yet it is in this age of globalization, in which information exchange is so widespread and accessible, that these systems of blending, assimilation, appropriation have become so visible. With the acknowledgement of institutionalised racism, analysing media representation and considering what stories it has to offer its many myriad audiences becomes important. Avatar: The Last Airbender has thus become a touchstone cartoon for its time as one that offers representation for Asian American audiences who grow up with marked faces, embedded in North American culture.

It is tempting to say that the Avatar universe is a hybridized version of our own, an example of East and West coming together to form a cohesive whole. Katara and Sokka come from the Southern Water Tribe, and audiences immediately identify their dark skin, their tundra home, and fur-lined clothing as markers of indigenous culture, the Inuit culture, specifically. Aang and the Air Nomad monks who raised him in high mountain plateaus are reminiscent of Tibetan monks. When Aang first encounters a vision of Toph, she is wearing a Tang Dynasty hanfu, signifying her Earth Kingdom merchant class upbringing.

At the same time, there are definite Americanisms running throughout the series: all the characters speak in English, with an “unmarked” accent that is associated with the generic American. In Book Two of the series, the characters meet swamp-dwelling waterbenders who sound like Appalachian rednecks, and a group of wanderers who are caricatures of the Flower Power, drug-addled hippie.

In writing about the hyphen, Peter Feng notes that it “preserves the notion of a duality of a binary opposition, a pattern of thinking which limits the answers to those posed by the question.” Feng’s essay fights for the right of the space that the hyphen is supposed to represent to remain a space that is not a bridge between two concepts, but a space from which something new can be created in the meeting between them.

I am going to suggest that the universe of Avatar: The Last Airbender, inhabits this hyphen, this interval, in its self-contained logic, offering a perspective on approaching identity that refuses immutability and resists stability. Its concepts offer an insight into a process of becoming that complicates binaristic, linear patterns of thought. I do this with the caveat that the production of the series by an American company, its creation by two Anglo males, a voice acting cast and writing crew comprised mainly of white Americans working with a Korean animation crew has completely different implications for the concept I work with. Although they require addressing, I want to focus solely on in-show elements for the purpose of this paper.

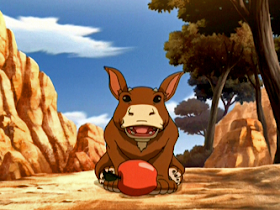

So, back to pangolin bears.

In this simpler example, the hybridity of the fauna is the combination of two separate animals into a new kind of animal, an unexpected chimera to the audience. No one, for example, expects Foo-Foo Cuddlypoops, playing with meat-eating Sokka while he is trapped in the ground, to be a sabre-toothed lion moose cub. When Sokka is surprised by this, having been told by Aang, it is not because he is aware of what a moose and a sabre-toothed lion are; it is because he is from the South Pole and has never had occasion to know that such creatures existed.

Hybridity fauna is only remarkable to the viewer, and utterly sensical to those in the ‘verse, offering a window into a world where Other’d groups do not live with their hybridity under scrutiny. Writing on polyculturalism, Vijay Prashad reminds us, that “cultural formations are not as discrete as is often assumed. [The term] hybrid ... retains ideas of purity and origins (two things melded together)” (53). The fauna in the Avatar universe are hybrid to us, who are aware of their discrete origins in the meta-worldbuilding of the universe. What, then, of less discrete concepts, such as culture?

The bending arts within the Avatar universe offer an interesting perspective. The concept of bending, upon which the plot of the series rests, is also an example of hybridization. Aang, the last airbender in the world, must master bending, or manipulating, air, water, earth and fire, in order to become a fully-realized Avatar. Each element is associated with a different martial art style. But the four-element system is not universal to all cultures. The Chinese and Tibetan cultures, for example, have five elements. This piece of trivia points to a conscious choice to go with a system more recognizable to young North America-based target audiences.

For the audience, the art of bending is a fantastic creation, but within the universe, it is as natural as the hybrid fauna. When a child calls Aang’s ability to glide through the air “magic,” he points out, “not magic, airbending.” Sokka, calls Katara’s waterbending skill “magic water,” and she has to remind him, “it’s part of our cultural heritage.” But these are noteworthy to in-universe characters not because bending is uncanny; it is because no one has seen an airbender in a hundred years, and because the Fire Nation has systematically captured all the waterbenders of the Southern Water Tribe, leaving Katara to grow up in an environment where there are none other than herself.

The naturalization of bending is more easily seen when the protagonists visit Omashu, an Earth Kingdom city-state, built on a mountain with tall chutes. Earthbenders guard the gates, which appear as empty walls. The chutes are part of the mailing system, on which carts delivering parcels and the like are moved up by earthbending, and brought down by gravity. As the series progresses, it reveals the metal industrialization that drives Fire Nation imperialism, and firebending powers this industrialization and its war machines. Within that universe, it is impossible to separate the fantastic from the mundane, as what we the audience might consider fantastic, is perfectly mundane. This is comforting as a perspective on Other’d cultures, versus one’s own. I’m sure we’ve encountered some variant of, “your culture is so interesting, it’s so different,” speaking of foreign cultures as fantastic, and somehow, not real.

The naturalization of bending is more easily seen when the protagonists visit Omashu, an Earth Kingdom city-state, built on a mountain with tall chutes. Earthbenders guard the gates, which appear as empty walls. The chutes are part of the mailing system, on which carts delivering parcels and the like are moved up by earthbending, and brought down by gravity. As the series progresses, it reveals the metal industrialization that drives Fire Nation imperialism, and firebending powers this industrialization and its war machines. Within that universe, it is impossible to separate the fantastic from the mundane, as what we the audience might consider fantastic, is perfectly mundane. This is comforting as a perspective on Other’d cultures, versus one’s own. I’m sure we’ve encountered some variant of, “your culture is so interesting, it’s so different,” speaking of foreign cultures as fantastic, and somehow, not real.

It has even more implications for the naturalization of Other’d cultures, the power of possibility for two, and more, seemingly contradictory things, to cohere. In the case of minority populations seeking integration and their younger generations, many often dealing with multi-racial, multi-cultural heritages, this seeming fiction is a reality many struggle to reconcile with. It calls for Prashad’s polyculturalism, which attempts to distance itself from multicultural rhetoric by acknowledging the porousness of culture, the fluidity, imagining the encounter as not between two or more static entities, but between multiple entities that are already influenced by each other in some form and must constantly re-negotiate with each other.

The construction of the Avatar within the Last Airbender universe lends a perspective to this dilemma that refuses the usual angst which accompanies the dysphoria of multiracialism. The Avatar is able to communicate with past lives. Every past life is a distinct character from the current Avatar. However, they are also understood to be part of the same person, the Avatar, who has access to some or all their memories, without being the “same person” in a linear fashion. Throughout the series, Aang encounters the previous Avatar, Roku, who is a character unto himself, but still one of Aang’s past lives. Aang must travel into a spiritual state to visit Roku, but Roku’s visitations are almost independent of Aang, coming when Aang needs him. This is not a contradiction in-universe. For those of us growing up with reincarnation in our cultural mythos, it is not a contradiction either.

The concept of the Avatar provides us with an entity onto which we can read our present points: as mediator of the past and the future, best exemplified when Roku summons Aang into visiting their shared past. In the episode “The Avatar and the Fire Lord,” Roku reveals to Aang his friendship with the Fire Nation leader Sozin who would eventually begin the war that Aang must end. “You inherited my problems and my mistakes. But I believe you are destined to redeem me,” Roku tells Aang. “Make sense of our past, and you will bring peace and balance to the world.” Similarly, someone with hyphenate identity may or may not have access to all the cultural knowledge that comes with that heritage. For example, an Asian American is still part of the non-American lineage. Yet they are still not Asian in the same sense that an Asian from Asia is Asian. Yet any cultural echoes from any of these identities may remain present.

Offering a way of understanding this is the concept of the Avatar as an entity belonging to all the nations. There is a cycle of the Avatar, and every Avatar is reborn into the next nation in the cycle. In both Aang and Roku’s stories, they travel to every nation other than their own to learn the different bending arts. This ensures a polycultural education for every Avatar, that each Avatar does not develop loyalty only to one nation. The idea is for the Avatar to become an impartial servant of all the peoples, settling their conflicts while ensuring that all of the nations remain autonomous. It is the violation of this principle, usually manifested in one nation trying to colonize and take over the other nations, that drives the conflicts that the last two Avatars faced, and the one which Aang must also face.

The separateness of the four different peoples in this universe is often emphasized. When first confronted with the beginnings of Fire Lord Sozin’s imperialistic ambitions, Avatar Roku insists, “the four nations are meant to be just that, four.” It doesn’t have to mean that the four nations are static, but it points to how multiculturalism needs to be a negotiation between multiple entities, not one entity benevolently extending its reach to engulf the others. General Iroh, in explaining a firebending defense technique, to his nephew, the disgraced and emotionally-conflicted Fire Nation Prince Zuko, says, “Understanding others, the other elements, and the other nations will help you become whole. ... It is the combination of the four elements in one person that makes the Avatar so powerful.”

The separateness of the four different peoples in this universe is often emphasized. When first confronted with the beginnings of Fire Lord Sozin’s imperialistic ambitions, Avatar Roku insists, “the four nations are meant to be just that, four.” It doesn’t have to mean that the four nations are static, but it points to how multiculturalism needs to be a negotiation between multiple entities, not one entity benevolently extending its reach to engulf the others. General Iroh, in explaining a firebending defense technique, to his nephew, the disgraced and emotionally-conflicted Fire Nation Prince Zuko, says, “Understanding others, the other elements, and the other nations will help you become whole. ... It is the combination of the four elements in one person that makes the Avatar so powerful.”

The Avatar, then is the living embodiment of multiculturalism, along with all the conflicts that arise, which involves a lack of easy answers. In one of the final episodes, Aang considers the fact that he is expected to kill Fire Lord Ozai, which goes against everything he has been taught. He consults four of his past lives: Roku, Kyoshi, Kuruk, and Yangchen. Roku’s advice to be decisive merely confuses him further. Kyoshi and Aang disagree on a technicality.

His attempt to contact an Avatar who shares his cultural background is interesting: Avatar Yangchen, the last Air Nomad Avatar before him, understands his desire to remain committed to the principles ingrained in him by the monks, but despite their shared cultural origins, tells him, “the Avatar’s sole duty is to the world. ... Selfless duty calls you to sacrifice your own spiritual needs and do whatever it takes to protect the world.” Each avatar’s approach is different, because they are informed by their own lifetimes and individual experiences.

Aang hasn’t lived their lives, and therefore must find his own solution. Many fans don’t find his final solution to make sense, since it came out of nowhere and seemed an easy way out for the writers to not have to deal with murder, but it can be read as Aang refusing a rote narrative assigned to him by the whole world, that in order to achieve justice, and end the war, he must take a life. Aang thus becomes a symbol for a departure from the past into an uncertain future. But this departure comes with a price for him, too.

When Aang returns to the Northern Air Temple, he finds everything different: pipes built into the murals depicting the history of his people; statue heads of sky bisons belching gas over pools of sewage; courtyards used for sacred rituals destroyed in front of his eyes. This process happens in the name of progress, adapting the living space for the Earth Kingdom refugees re-building their own lives. Aang is enraged by the destruction, and his attempt to hang onto his memories of how the place “really” is, points to the desire to pin down the reality of the existence of the Air Nomads as they were, and is thus in conflict with the need of another population to survive as they currently are.

When Aang demands, “who said you could be here?” he asks on behalf of the entire population of Air Nomads who see their heritage desecrated; the question is simpler for him, because he represents a population of one. It is easier for him to reconcile with the fact that the Northern Air Temple is being changed and inhabited without his sayso. In contrast, it is harder for diasporic and assimilated populations to know and remember stories, only to attempt a return and find everything completely different. There is no return, only a re-discovery.

Aang’s hero’s journey is thus not only about fixing the world, but about reconciling what he remembers of the world before he was stuck in an iceberg for one hundred years, with what he is seeing now, and dealing with the loss of his world, in the process of becoming the Avatar. Part of his duty to the world is to enable others in need, such as the wheelchair-using Teo, to build their lives in the airborne world Aang’s people once inhabited while he in turn also re-constructs his people’s airbending ways. The push and pull of two different identities move in seeming conflict, creating a new force, a new shape. It forces us to re-think what discrete and stable forces really mean, and what can be grown from their meeting.

Avatar: The Legend of Korra has recently started airing on Nickelodeon, and in the opening, Tenzin, Aang’s son, says, “like the changing of the seasons, the Avatar cycle begins anew.” Korra, the new Avatar, will take her place in a long line of Avatars before her, serving their function in the world as protector of the balance. She is Aang, Roku, Kyoshi, Kuruk, Yangchen, reborn; the same spirit, the same person, the same vessel of all the memories of past Avatars, in a different era, a different life, a different story, a different personality. The complexity of becoming calls for us to recognize this not as a contradiction, but as an ever-shifting space in a seeming dichotomy of difference. Korra’s story is not Aang’s story; there will be no rote action, no same steps she can take to maintain balance. It is informed and shaped by the past, and the forging of an always-uncertain future.

Keep in mind that this is just the talk and not as well-developed as I would like it to be... I may change the focus for the published piece, depending on feedback. If you see a point you would like to see expanded, let me know!

GIF set above reads:

Katara: The king is having a party at his palace tonight for his pet bear.

Aang: You mean, platypus bear?

Katara: No, it just says bear.

Sokka: Certainly you mean his skunk bear.

Toph: Or his armadillo bear?

Aang: Gopher bear?

Katara: Just... bear.

Toph: This place is weird.

The puzzlement towards The Bear that has only one aspect is a source of humour to audiences who are familiar with systems in which we can definitively declare something with a single aspect. In world-building exercises, writers are encouraged to draw directly from their knowledge and experiences, to reconstitute it into something different. This moment in the series was my starting point in considering how we often unthinkingly extend this understanding to something as fluid as concepts of culture and ethnicity.

Mass migration is not new, nor is cultural exchange. Yet it is in this age of globalization, in which information exchange is so widespread and accessible, that these systems of blending, assimilation, appropriation have become so visible. With the acknowledgement of institutionalised racism, analysing media representation and considering what stories it has to offer its many myriad audiences becomes important. Avatar: The Last Airbender has thus become a touchstone cartoon for its time as one that offers representation for Asian American audiences who grow up with marked faces, embedded in North American culture.

It is tempting to say that the Avatar universe is a hybridized version of our own, an example of East and West coming together to form a cohesive whole. Katara and Sokka come from the Southern Water Tribe, and audiences immediately identify their dark skin, their tundra home, and fur-lined clothing as markers of indigenous culture, the Inuit culture, specifically. Aang and the Air Nomad monks who raised him in high mountain plateaus are reminiscent of Tibetan monks. When Aang first encounters a vision of Toph, she is wearing a Tang Dynasty hanfu, signifying her Earth Kingdom merchant class upbringing.

At the same time, there are definite Americanisms running throughout the series: all the characters speak in English, with an “unmarked” accent that is associated with the generic American. In Book Two of the series, the characters meet swamp-dwelling waterbenders who sound like Appalachian rednecks, and a group of wanderers who are caricatures of the Flower Power, drug-addled hippie.

In writing about the hyphen, Peter Feng notes that it “preserves the notion of a duality of a binary opposition, a pattern of thinking which limits the answers to those posed by the question.” Feng’s essay fights for the right of the space that the hyphen is supposed to represent to remain a space that is not a bridge between two concepts, but a space from which something new can be created in the meeting between them.

I am going to suggest that the universe of Avatar: The Last Airbender, inhabits this hyphen, this interval, in its self-contained logic, offering a perspective on approaching identity that refuses immutability and resists stability. Its concepts offer an insight into a process of becoming that complicates binaristic, linear patterns of thought. I do this with the caveat that the production of the series by an American company, its creation by two Anglo males, a voice acting cast and writing crew comprised mainly of white Americans working with a Korean animation crew has completely different implications for the concept I work with. Although they require addressing, I want to focus solely on in-show elements for the purpose of this paper.

So, back to pangolin bears.

In this simpler example, the hybridity of the fauna is the combination of two separate animals into a new kind of animal, an unexpected chimera to the audience. No one, for example, expects Foo-Foo Cuddlypoops, playing with meat-eating Sokka while he is trapped in the ground, to be a sabre-toothed lion moose cub. When Sokka is surprised by this, having been told by Aang, it is not because he is aware of what a moose and a sabre-toothed lion are; it is because he is from the South Pole and has never had occasion to know that such creatures existed.

Hybridity fauna is only remarkable to the viewer, and utterly sensical to those in the ‘verse, offering a window into a world where Other’d groups do not live with their hybridity under scrutiny. Writing on polyculturalism, Vijay Prashad reminds us, that “cultural formations are not as discrete as is often assumed. [The term] hybrid ... retains ideas of purity and origins (two things melded together)” (53). The fauna in the Avatar universe are hybrid to us, who are aware of their discrete origins in the meta-worldbuilding of the universe. What, then, of less discrete concepts, such as culture?

The bending arts within the Avatar universe offer an interesting perspective. The concept of bending, upon which the plot of the series rests, is also an example of hybridization. Aang, the last airbender in the world, must master bending, or manipulating, air, water, earth and fire, in order to become a fully-realized Avatar. Each element is associated with a different martial art style. But the four-element system is not universal to all cultures. The Chinese and Tibetan cultures, for example, have five elements. This piece of trivia points to a conscious choice to go with a system more recognizable to young North America-based target audiences.

For the audience, the art of bending is a fantastic creation, but within the universe, it is as natural as the hybrid fauna. When a child calls Aang’s ability to glide through the air “magic,” he points out, “not magic, airbending.” Sokka, calls Katara’s waterbending skill “magic water,” and she has to remind him, “it’s part of our cultural heritage.” But these are noteworthy to in-universe characters not because bending is uncanny; it is because no one has seen an airbender in a hundred years, and because the Fire Nation has systematically captured all the waterbenders of the Southern Water Tribe, leaving Katara to grow up in an environment where there are none other than herself.

The naturalization of bending is more easily seen when the protagonists visit Omashu, an Earth Kingdom city-state, built on a mountain with tall chutes. Earthbenders guard the gates, which appear as empty walls. The chutes are part of the mailing system, on which carts delivering parcels and the like are moved up by earthbending, and brought down by gravity. As the series progresses, it reveals the metal industrialization that drives Fire Nation imperialism, and firebending powers this industrialization and its war machines. Within that universe, it is impossible to separate the fantastic from the mundane, as what we the audience might consider fantastic, is perfectly mundane. This is comforting as a perspective on Other’d cultures, versus one’s own. I’m sure we’ve encountered some variant of, “your culture is so interesting, it’s so different,” speaking of foreign cultures as fantastic, and somehow, not real.

The naturalization of bending is more easily seen when the protagonists visit Omashu, an Earth Kingdom city-state, built on a mountain with tall chutes. Earthbenders guard the gates, which appear as empty walls. The chutes are part of the mailing system, on which carts delivering parcels and the like are moved up by earthbending, and brought down by gravity. As the series progresses, it reveals the metal industrialization that drives Fire Nation imperialism, and firebending powers this industrialization and its war machines. Within that universe, it is impossible to separate the fantastic from the mundane, as what we the audience might consider fantastic, is perfectly mundane. This is comforting as a perspective on Other’d cultures, versus one’s own. I’m sure we’ve encountered some variant of, “your culture is so interesting, it’s so different,” speaking of foreign cultures as fantastic, and somehow, not real.It has even more implications for the naturalization of Other’d cultures, the power of possibility for two, and more, seemingly contradictory things, to cohere. In the case of minority populations seeking integration and their younger generations, many often dealing with multi-racial, multi-cultural heritages, this seeming fiction is a reality many struggle to reconcile with. It calls for Prashad’s polyculturalism, which attempts to distance itself from multicultural rhetoric by acknowledging the porousness of culture, the fluidity, imagining the encounter as not between two or more static entities, but between multiple entities that are already influenced by each other in some form and must constantly re-negotiate with each other.

The construction of the Avatar within the Last Airbender universe lends a perspective to this dilemma that refuses the usual angst which accompanies the dysphoria of multiracialism. The Avatar is able to communicate with past lives. Every past life is a distinct character from the current Avatar. However, they are also understood to be part of the same person, the Avatar, who has access to some or all their memories, without being the “same person” in a linear fashion. Throughout the series, Aang encounters the previous Avatar, Roku, who is a character unto himself, but still one of Aang’s past lives. Aang must travel into a spiritual state to visit Roku, but Roku’s visitations are almost independent of Aang, coming when Aang needs him. This is not a contradiction in-universe. For those of us growing up with reincarnation in our cultural mythos, it is not a contradiction either.

The concept of the Avatar provides us with an entity onto which we can read our present points: as mediator of the past and the future, best exemplified when Roku summons Aang into visiting their shared past. In the episode “The Avatar and the Fire Lord,” Roku reveals to Aang his friendship with the Fire Nation leader Sozin who would eventually begin the war that Aang must end. “You inherited my problems and my mistakes. But I believe you are destined to redeem me,” Roku tells Aang. “Make sense of our past, and you will bring peace and balance to the world.” Similarly, someone with hyphenate identity may or may not have access to all the cultural knowledge that comes with that heritage. For example, an Asian American is still part of the non-American lineage. Yet they are still not Asian in the same sense that an Asian from Asia is Asian. Yet any cultural echoes from any of these identities may remain present.

Offering a way of understanding this is the concept of the Avatar as an entity belonging to all the nations. There is a cycle of the Avatar, and every Avatar is reborn into the next nation in the cycle. In both Aang and Roku’s stories, they travel to every nation other than their own to learn the different bending arts. This ensures a polycultural education for every Avatar, that each Avatar does not develop loyalty only to one nation. The idea is for the Avatar to become an impartial servant of all the peoples, settling their conflicts while ensuring that all of the nations remain autonomous. It is the violation of this principle, usually manifested in one nation trying to colonize and take over the other nations, that drives the conflicts that the last two Avatars faced, and the one which Aang must also face.

The separateness of the four different peoples in this universe is often emphasized. When first confronted with the beginnings of Fire Lord Sozin’s imperialistic ambitions, Avatar Roku insists, “the four nations are meant to be just that, four.” It doesn’t have to mean that the four nations are static, but it points to how multiculturalism needs to be a negotiation between multiple entities, not one entity benevolently extending its reach to engulf the others. General Iroh, in explaining a firebending defense technique, to his nephew, the disgraced and emotionally-conflicted Fire Nation Prince Zuko, says, “Understanding others, the other elements, and the other nations will help you become whole. ... It is the combination of the four elements in one person that makes the Avatar so powerful.”

The separateness of the four different peoples in this universe is often emphasized. When first confronted with the beginnings of Fire Lord Sozin’s imperialistic ambitions, Avatar Roku insists, “the four nations are meant to be just that, four.” It doesn’t have to mean that the four nations are static, but it points to how multiculturalism needs to be a negotiation between multiple entities, not one entity benevolently extending its reach to engulf the others. General Iroh, in explaining a firebending defense technique, to his nephew, the disgraced and emotionally-conflicted Fire Nation Prince Zuko, says, “Understanding others, the other elements, and the other nations will help you become whole. ... It is the combination of the four elements in one person that makes the Avatar so powerful.”The Avatar, then is the living embodiment of multiculturalism, along with all the conflicts that arise, which involves a lack of easy answers. In one of the final episodes, Aang considers the fact that he is expected to kill Fire Lord Ozai, which goes against everything he has been taught. He consults four of his past lives: Roku, Kyoshi, Kuruk, and Yangchen. Roku’s advice to be decisive merely confuses him further. Kyoshi and Aang disagree on a technicality.

His attempt to contact an Avatar who shares his cultural background is interesting: Avatar Yangchen, the last Air Nomad Avatar before him, understands his desire to remain committed to the principles ingrained in him by the monks, but despite their shared cultural origins, tells him, “the Avatar’s sole duty is to the world. ... Selfless duty calls you to sacrifice your own spiritual needs and do whatever it takes to protect the world.” Each avatar’s approach is different, because they are informed by their own lifetimes and individual experiences.

Aang hasn’t lived their lives, and therefore must find his own solution. Many fans don’t find his final solution to make sense, since it came out of nowhere and seemed an easy way out for the writers to not have to deal with murder, but it can be read as Aang refusing a rote narrative assigned to him by the whole world, that in order to achieve justice, and end the war, he must take a life. Aang thus becomes a symbol for a departure from the past into an uncertain future. But this departure comes with a price for him, too.

When Aang returns to the Northern Air Temple, he finds everything different: pipes built into the murals depicting the history of his people; statue heads of sky bisons belching gas over pools of sewage; courtyards used for sacred rituals destroyed in front of his eyes. This process happens in the name of progress, adapting the living space for the Earth Kingdom refugees re-building their own lives. Aang is enraged by the destruction, and his attempt to hang onto his memories of how the place “really” is, points to the desire to pin down the reality of the existence of the Air Nomads as they were, and is thus in conflict with the need of another population to survive as they currently are.

When Aang demands, “who said you could be here?” he asks on behalf of the entire population of Air Nomads who see their heritage desecrated; the question is simpler for him, because he represents a population of one. It is easier for him to reconcile with the fact that the Northern Air Temple is being changed and inhabited without his sayso. In contrast, it is harder for diasporic and assimilated populations to know and remember stories, only to attempt a return and find everything completely different. There is no return, only a re-discovery.

Aang’s hero’s journey is thus not only about fixing the world, but about reconciling what he remembers of the world before he was stuck in an iceberg for one hundred years, with what he is seeing now, and dealing with the loss of his world, in the process of becoming the Avatar. Part of his duty to the world is to enable others in need, such as the wheelchair-using Teo, to build their lives in the airborne world Aang’s people once inhabited while he in turn also re-constructs his people’s airbending ways. The push and pull of two different identities move in seeming conflict, creating a new force, a new shape. It forces us to re-think what discrete and stable forces really mean, and what can be grown from their meeting.

Avatar: The Legend of Korra has recently started airing on Nickelodeon, and in the opening, Tenzin, Aang’s son, says, “like the changing of the seasons, the Avatar cycle begins anew.” Korra, the new Avatar, will take her place in a long line of Avatars before her, serving their function in the world as protector of the balance. She is Aang, Roku, Kyoshi, Kuruk, Yangchen, reborn; the same spirit, the same person, the same vessel of all the memories of past Avatars, in a different era, a different life, a different story, a different personality. The complexity of becoming calls for us to recognize this not as a contradiction, but as an ever-shifting space in a seeming dichotomy of difference. Korra’s story is not Aang’s story; there will be no rote action, no same steps she can take to maintain balance. It is informed and shaped by the past, and the forging of an always-uncertain future.

fantastic post, jha! I loved it.

ReplyDelete~arvan

a thought-provoking theoretical analysis. i'll never look at pangolin-bears or aardvark-sloths the same way again! do you think perhaps the downside (or perhaps misuse) of this polycultural fluidity in Airbender, might explain (in part) the almost obsessive tendency to "racebend" its characters--where the normalization of the usually "other" allows some (from the movie to fanart) to imagine them as "white" in a society where "white" is the perceived normal/default? i'd be interested in reading any future observations you have on the new series Legend of Korra, as this shift from a steampunk to dieselpunk four kingdoms has certainly forged "an uncertain future" and a decided "demographic" shift: a lot more characters in this series seem to bend towards those "Appalachians," even if they don't sound like them, if you catch my drift...

ReplyDeleteNaw, I think the tendency to whitewash is straight up white supremacy since it's really unfair to assume white=default the way a significant part of ATLA fandom does. But I definitely see how polyculturalism, like multiculturalism, can be abused in favour of whitewashing. It's one of the things I've been working through for a while and I still have no real answers on how to address that. Hence why I'm going back to school, heh.

DeleteI don't really draw much comparison between Republic City and any Western city, but rather to Hon Kong and Shanghai. There're a lot of really great things said about Republic City at the ATLA-Annotated Tumblr, if you're interested.